Tyler, when I moved back to Birmingham last summer, I remember just missing the interactive art exhibit “All In” at Ramsay Highschool, produced by 1504 and The Birmingham Education Foundation. I was struck by how thoughtful the work was. And that’s where I’d like to begin our discussion.

Tyler, when I moved back to Birmingham last summer, I remember just missing the interactive art exhibit “All In” at Ramsay Highschool, produced by 1504 and The Birmingham Education Foundation. I was struck by how thoughtful the work was. And that’s where I’d like to begin our discussion.

You talk a lot about bridging the gap between strategy and creativity. I think most folks assume each of those are assigned to either the right or left brain, but the crossover is where the magic happens. How do you meld the two? What are key parts of your discovery process that point you towards the best artistic outcome?

I love talking about this and am glad it resonates. I believe that too often strategy becomes siloed from creativity and leads to work that’s not as responsive. At 1504, when we think about strategy, we think about the perception we’re trying to shift through storytelling. So in an exhibit like “All In” we wanted to build empathy and give people a new perspective through experience.

Ultimately, the bridging of the two is about centering on the intention of the story and how we can produce content that’s not just content for content’s sake. We don’t want to add noise. We want to put something in the world that moves someone. We want to be thoughtful in our work, not just reactive.

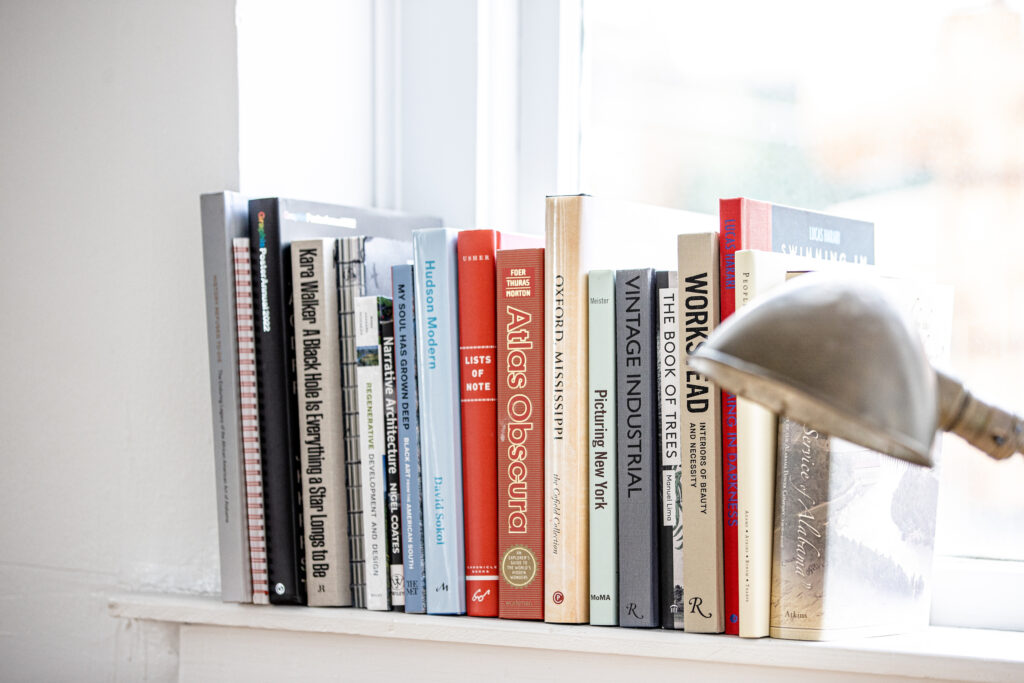

If you have the right amount of time to really listen and sink into a story, there is no hard stop between strategy and creative process. You can find ways to do both simultaneously. We do very in-depth site visits and immerse ourselves in the shoes of people we’re working with. No cameras, just time in the space with the people we’re connecting with. That’s the journalistic aspect of our work and a lot of us have journalism backgrounds.

When it’s a conversation with a commercial partner, we try to rewind the convo away from the content and back to the blueprint of the desired outcomes. We have to slow down to uncover all the different mediums that speak to their desired outcomes. We’ve been fortunate to work with a lot of people who are open to going through this slow and meaningful process. And that makes us a nontraditional production company that allows for a more comprehensive approach to storytelling.

Empathy is thematic in your work. Why is that a central theme and how do you transform it into something interactive?

Most of the power in storytelling lies in the heart of facilitating connection. Stories connect us to each other and to our sense of self. Art helps us navigate the world. We’ve seen a lot of opportunities to use storytelling to foster empathy.

Part of that comes from being aware of our time and place, living in Birmingham, Alabama in 2022, for example. We are all aware of how fractured our society and institutions are, so stories are a great way to get people to listen and nurture compassion. We can ask questions that encourage compassionate responses to better appreciate someone else’s experience. That’s why empathy is a thread in our work. It’s our mission to do our part to build a more empathetic society.

Part of that comes from being aware of our time and place, living in Birmingham, Alabama in 2022, for example. We are all aware of how fractured our society and institutions are, so stories are a great way to get people to listen and nurture compassion. We can ask questions that encourage compassionate responses to better appreciate someone else’s experience. That’s why empathy is a thread in our work. It’s our mission to do our part to build a more empathetic society.

As far as how you can create interactive experiences with empathy, I think it is tied to moving beyond passive content like videos. We’re inundated with videos, so we’ve been thinking about how to use digital content in the real world to have a more participatory, place-based watching experience. When we can put people in the place of the story, it adds another layer of meaning. It’s another way to create historic connection and give people an opportunity to feel and know the place of the person’s experience.

We credit a lot of learnings about how to leverage space through working with the Equal Justice Initiative. The EJI’s memorial and museum’s immersive design principles change the vantage point and we want our work to mimic that immersive quality, so you lose yourself in a story.

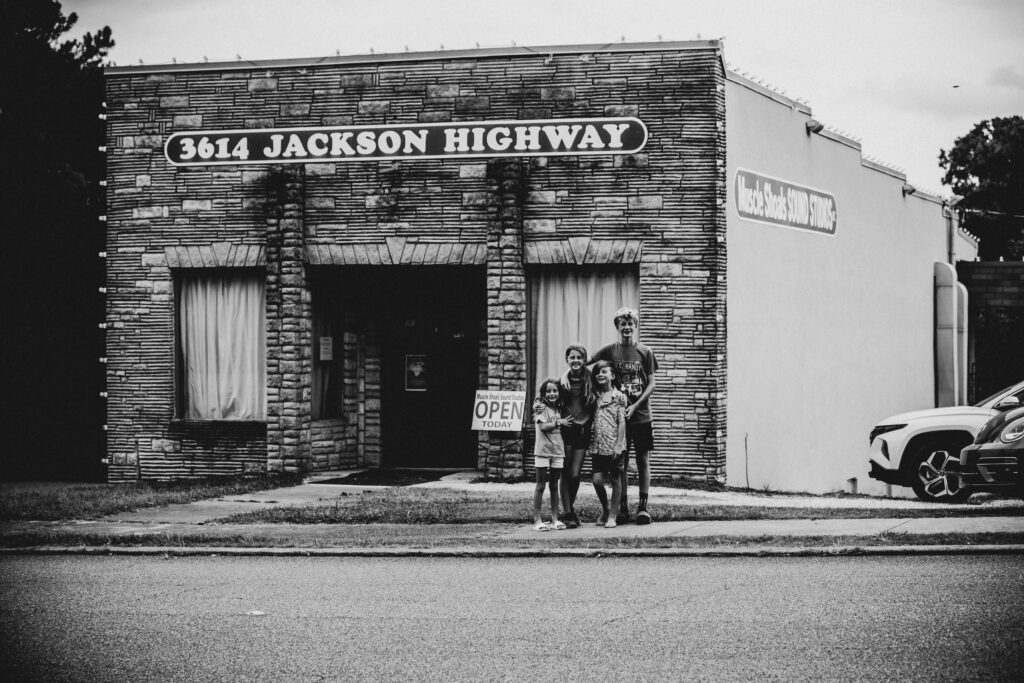

Was there ever a moment in your childhood or education that made you think about processing and leveraging art in this way?

It was this chilling moment of connection where I saw my hometown and Alabama in a new light. That experience involved all the ingredients of crossing a threshold, mainly a little risk and a little vulnerability, into a new view of music. It was transformative. I didn’t have the language then, but now I think of that as experience design and that’s what we aspire to do as a studio. It just takes different shapes.

One of your current projects is a collaboration with the Gadsden Museum of Art. Tell us about “Finches”.

One of your current projects is a collaboration with the Gadsden Museum of Art. Tell us about “Finches”.

The installation is a project led by Melissa Yes, Fen Kennedy, Todd Slaughter and myself with a growing list of collaborators. The premise is using the myth of Atticus Finch to explore the complex and problematic characters in our life. He’s kind of a standard of moral guidance, and yet, in Harper Lee’s earlier drafted transcript, we learned that Atticus Finch is a white supremacist.

What do we do when a person or place we love lets us down? How do we reconcile ourselves with complicated truths and still hold people accountable? Who do we typically put on pedestals and what voices have been silenced in doing that? Those questions are being explored in this installation. A lot of it is very participatory and there is iconography that connects to Alabama and Monroeville.

It’s in the Gadsden Museum of Art and on the 20th of August there is a live dance performance happening inside the museum with dancers from the University of Alabama. Fen Kennedy developed and choreographed the dance piece. It’s been a great collaboration and will end on the 26th of August.

That sounds like a wonderful exploration. Are there any other current projects in the pipeline you’d like to discuss?

We’re working on a civil rights project at Temple Beth-El. They’ve been doing a lot of work to tell the story of the attempted bombing in 1958. We want to create a space for people to have a Jewish lens on the civil rights movement in Birmingham. They played a role in that movement. The exhibit dates are still to be determined, but we will host a preview photo event on August 25th with photographs by Spider Martin.

It’s the first time that this collection has been loaned out on display!

The challenge of loving flawed things is an inescapable part of the human experience. What is a flawed thing that you love and grapple with? Was it that thing that inspired this relationship to Harper Lee’s work?

For me, it always comes back to a really complicated relationship with Alabama. And the tension between the natural beauty of this place and the beauty of its people, food, architecture etc., coexisting with the history of violence here. How do you reconcile those two things in this place?I hold them in tension and think less about reconciling them. How can we hold things in tension and let these dualities exist? That’s very inescapable here in Alabama. We’re constantly reminded of the disparities and shortcomings here. We try to love this place and do the work… Ashley M. Jones does a much better job articulating this idea in her poetry. She does amazing work around navigating the tensions of being southern and the messiness of that.

A quote I think of often is from The Last Black Man in San Francisco, when Jimmie Fails says, “You don’t get to hate it unless you love it,” in response to someone critiquing the city and that’s sort of reminiscent of the South. We hope to do regenerative work while not being naive or unrealistic.