Klein Arts & Culture, in Harpersville, Alabama, provides a venue to facilitate racial reconciliation through the arts and education. The organization is converting a remnant of America’s racist past into a symbol of a more equitable future by engaging in activities that raise consciousness about race through dance, music, poetry, visual arts, and education. We had the chance to sit down and discuss this work with Klein Arts and Culture President Theangelo Perkins and Executive Director Nell Gottlieb, who are co-founders of the organization.

I’d like to ask you both some questions individually before we get into your work together at Klein.

I’d like to ask you both some questions individually before we get into your work together at Klein.

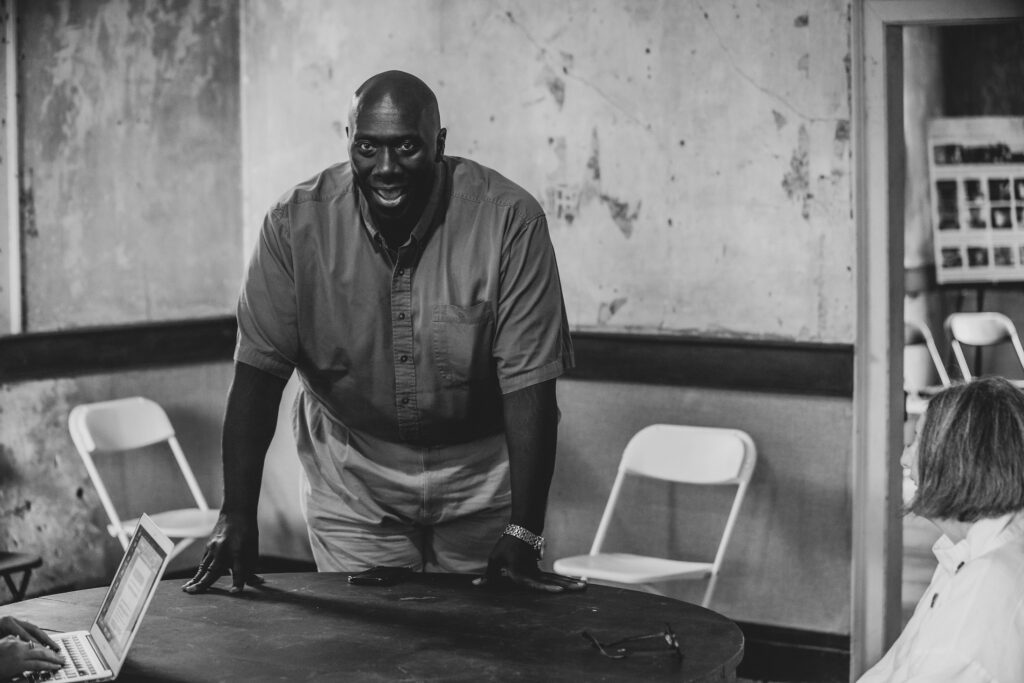

Mr. / Mayor/ Pastor Theo Perkins, you are well known for doing it all. You literally drive the school bus, lead the town, have a real estate business, are the President of this organization, and the founding Pastor of Liberty Christian Church. Why?

Theo: I have love for my town and my community. It’s all about service. It’s all about community. And I know that I’m called to serve in every one of those capacities. With the church, it’s about uplifting people. In real estate, it’s seeing the joy in people’s faces when they realize they can own a home, and I can help them achieve something they’ve always wanted to achieve.

Now bus drivers… bus drivers are the only people that have all their troubles behind them. But seriously, it’s still an extension of service. I give a speech to the kids every morning. I tell them, you’re not here to eat, sleep, socialize, or court. You’re here to get an education. Have a great day.

I know this is my calling. And sometimes, it’s tough, but when you know what you’re called to do, it makes it easier. You know, people ask, “Why haven’t you left?” There is an obvious answer. What are you going to give back? How can you break the cycle? It’s easy to leave. But you have to give back.

What was it like growing up in Harpersville? What sparked your interest in the history of your hometown?

Theo: Listen, my upbringing probably sparked my interest in history. In a small town where everybody knows everybody, it can be both positive and negative. I remember doing a family tree in middle school. My dad told me all about his parents and grandparents. Ever since then, I have been interested in my family and heritage. I also had a great-grandmother who would just sit down and tell us stories. And some of my family would joke about it, saying, “Here she goes,” but I listened. I really listened to her. And it was interesting to hear her talk about her grandparents. She was born in 1907, so those grandparents were born in the 1840s and 1850s.

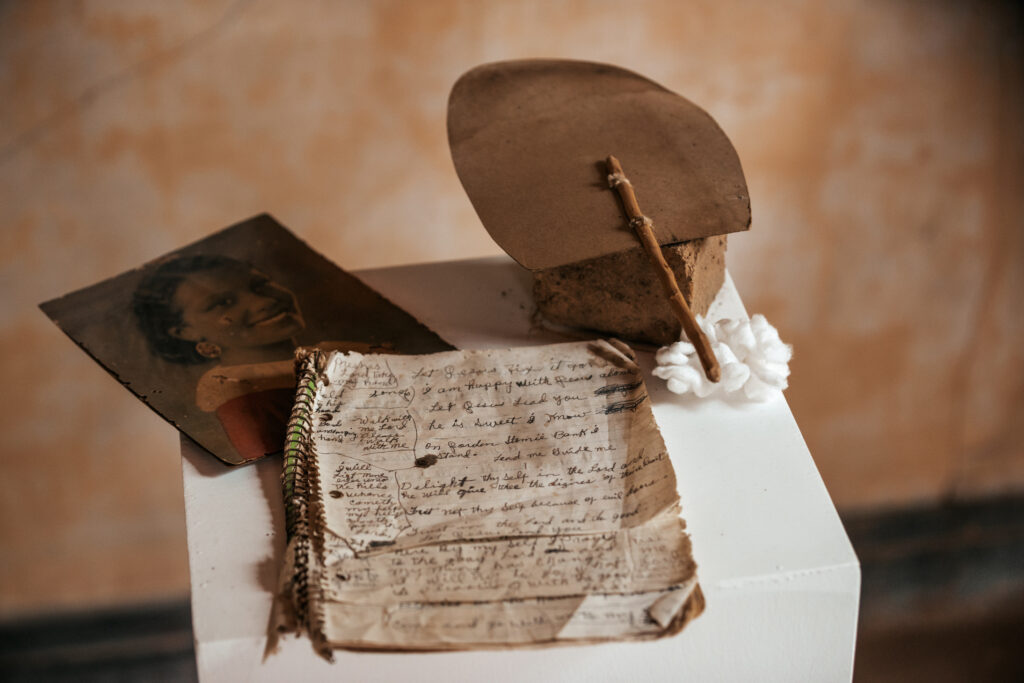

And my relationship to this place. My grandmother, by the way, worked in this house in the 1930s. She was also the Avon lady and went all over town. My great great grandfather came to work on the Wallace farm in 1870, right after emancipation. They lived on this property for many, many years. My last relative, who worked at the Wallace House, died in the 1990s, so for 125 years, my family has been on this property. My great-grandfather and his brother actually ran the farm for Nell’s aunts.

Nell: Yes, I knew them and learned to cook from Theo’s great-aunt.

Nell, you grew up in Birmingham and spent your childhood summers in Harpersville. When you left Alabama, you vowed never to come back. Yet, here we are.

What was your experience as a girl here? Where did you go when you left?

Nell: As a girl, I was raised in a single-parent home, so I came here with my grandmother every summer by myself. The house wasn’t lived in during the winters. We’d sleep downstairs, get water from the well, etc. It was a true country experience. There was a caretaker, Mr. John Mallery, who lived on the property. He was one of the first black people I knew, and we became close. He was actually the one who told me when my dog died.

Life was very simple. When I first came out, I’d toughen up my feet so I could run barefoot. My best friend and I went every day to swim in the creek. The creek kept us clean, and every Sunday, we’d go to my great Aunt’s house and have a bath since they had indoor plumbing. We played every day together, sharing stacks of watermelons with the hogs. It was amazing. It was the best living you could have.

Life was very simple. When I first came out, I’d toughen up my feet so I could run barefoot. My best friend and I went every day to swim in the creek. The creek kept us clean, and every Sunday, we’d go to my great Aunt’s house and have a bath since they had indoor plumbing. We played every day together, sharing stacks of watermelons with the hogs. It was amazing. It was the best living you could have.

When I left Alabama, I went to Atlanta first. That was all my mother and grandmother said I could do. From Emory, I went to New York and attended Rockefeller University. I fell in love and dropped out. My husband was a Jewish New Yorker. We eventually moved to Palo Alto, to Boston, and then to Austin, Texas, in 1980, where I still reside today.

What brought you back to Alabama? And when did you become interested in the history of this place?

Nell: I was always interested in the history of this place, and it was fed down my throat. I was brought up hearing about the “Lost Cause.” The complexity of it, in one way, escaped me, and in another way, it didn’t because I went on to graduate school in sociology. I spent the whole semester of my freshman year trying to figure out the apartheid nation that I was actually living in. I had never questioned the order of things. I was just a fish in water. But Sociology 101 was the beginning of it all.

It was years later that I got a Ph.D. in Sociology at Boston University. I taught public health education for thirty years. While that’s all about social justice, it was still conceptual and not about Alabama specifically.

What really changed for me was in 2012 during my high school reunion. I went to Ramsay. I started asking people what they knew about the Civil Rights Movement. They knew so little, and shocking and strange as it was, it was true. That set me off.

What really changed for me was in 2012 during my high school reunion. I went to Ramsay. I started asking people what they knew about the Civil Rights Movement. They knew so little, and shocking and strange as it was, it was true. That set me off.

I retired in 2011 and went to art school in Houston. I started doing work based on imagery through Birmingham. And then I got a lot of feedback that I was appropriating black pain. So in 2018, I thought about what I really knew.

That was the same year my cousin called about the house, and he said he wanted me to have it. I finally agreed to take the house after several years of saying no. It was a litany of woes, but I knew I wanted to do something with this.

Some family from New York and California came down after I inherited the house. That’s when Theo walked in.

Theo: I heard the family was here, and I wanted to greet and meet them.

Let’s talk about the conversation you all had following that greeting. The one in the family cemetery. Theo, you brought up the issue of access to Nell, as Nell’s predecessors had closed the black portion of the cemetery off except for two days per year. What happened in that first meeting at the cemetery?

Let’s talk about the conversation you all had following that greeting. The one in the family cemetery. Theo, you brought up the issue of access to Nell, as Nell’s predecessors had closed the black portion of the cemetery off except for two days per year. What happened in that first meeting at the cemetery?

Theo: At the cemetery, I told Nell and the family that it had been blocked off to the black community. My grandparents and great-grandparents are buried there. My great great great grandparents are buried there. For years we took care of the black part of the cemetery, but another cousin came to town and said they’d take care of it from now on, so we no longer had a key.

He put up a second gate and said he’d open it for Mother’s Day and Father’s Day. We had relatives that came home to visit, and they couldn’t get into the cemetery. So told Nell and her family at the cemetery that this has happened and we need to do something.

Right away, they told the caretaker to cut the lock and open the gate. And that was it. That started our conversation. The lock was cut, and the gate was opened.

We then asked what we could do with the house and the property.

Nell: My family from across the US were at the house that June when our conversation at the cemetery happened. We knew that we had to bring people back into the cemetery. So in October of 2018, we brought families, both black and white, to the Wallace cemetery.

Nell: My family from across the US were at the house that June when our conversation at the cemetery happened. We knew that we had to bring people back into the cemetery. So in October of 2018, we brought families, both black and white, to the Wallace cemetery.

Theo: The descendants, both black and white, came to that homecoming. And Nell and her family gave the key to the descendants. It was really beautiful. All the names were called.

Nell: We named the people that were buried. We lay a wreath for all of the unnamed black people who were buried in the cemetery. Unlike the black cemetery, the white cemetery had been maintained all of the time.

Nell, why do you think you were the first in your family to take that step?

Nell: Because I left. That’s why. Because I was the most liberal person in my part of the family. I had been along the path of opening my eyes a bit. Also, inheriting Jewish tradition influenced me.

My daughter, when she was young, used to say Daddy’s Jewish and Mommy’s Southern.

I didn’t come back for a long time. There were a lot of people in my family who weren’t that nice to me. They were racist and anti-semitic. Even when I was young, I thought I’d been born into the wrong family. I used to tell people I was from England.

I didn’t come back for a long time. There were a lot of people in my family who weren’t that nice to me. They were racist and anti-semitic. Even when I was young, I thought I’d been born into the wrong family. I used to tell people I was from England.

Regardless, our family all know and remember Will McGinnis for teaching us everything.

Theo: Yes! I had lots of pictures of little white kids who we didn’t know. And Nell had pictures of my family that I didn’t have.

Nell: We have generations of white families on the porch, and now we have black and white porch pictures during our family reunions.

Speaking of family reunions, how was that first gathering in October of 2018? What emotions did you both have approaching the gathering?

Nell: I didn’t know what to expect. I’ll say that. We had it carefully planned and had T. Marie King, from Birmingham, as a facilitator. My whole family came. I was anxious, but we all got caught up in the service and sang together. Theo led us in Fly Away. At the moment of the gate key exchange, there wasn’t a dry eye in the place.

The man who received the key to the cemetery had both his enslaved grandfather and son buried there. When we came back to the house, T. Marie led the conversation, and we ate BBQ together.

Theo: Well, we had planned and were hoping for a good turnout. But we didn’t know how people were going to react. We didn’t know if people were going to be engaged and were pleasantly surprised at the cemetery when there was a coming together and unifying. It was powerful to think about the circle of people. The descendants of the enslaved with the descendants of the slave owners. And they were coming together. And it was amazing. Some of the people, especially some of the black people that came, said that they never thought that this could happen or that this would happen.

Theo: Well, we had planned and were hoping for a good turnout. But we didn’t know how people were going to react. We didn’t know if people were going to be engaged and were pleasantly surprised at the cemetery when there was a coming together and unifying. It was powerful to think about the circle of people. The descendants of the enslaved with the descendants of the slave owners. And they were coming together. And it was amazing. Some of the people, especially some of the black people that came, said that they never thought that this could happen or that this would happen.

Nell: There is a lot of ritual at the cemetery. We do a call and response across the black-and-white cemetery. We add new people to the list as well so they can become part of the annual ritual.

Ritual plays a big part of it. Having Theo’s leadership has been really important. And Theo is a trained historian who also has a history with this house.

At its height, there were 90 enslaved people here. And four or five of those families still live in the area. There is a huge wealth of memories that live on that we can archive.

Do black and white descendants get together annually?

Nell: We get together every October, outside of covid. And this year will be our fourth reunion. 40-50 people come annually. We want to do a whole weekend so folks from far away can come.

Sitting here together is different than sitting anywhere else.

In your early conversations, was there a clear goal and mission for The Wallace House? Or did it unfold in time?

Theo: No. We didn’t know when we first met. We just began to talk after the gate lock was cut. Once the gate was open, so was our conversation. That led to the homecoming, and our plan was birthed after that. We wanted to know how we can make a difference.

Nell: I brought the art part to it and wanted to know what could be done with it in terms of the art piece while still serving the main goal. I was making the rounds for art, and then the dance residency fell into our laps. The contractor worked around the clock to get the house ready for dancers. We had to make sure the floorboards were secure.

The dance event was actually supposed to be in Arlington House, but the furnishings posed a problem, and they couldn’t do it there. So we were able to host it, and that’s what put us on the map. It was in January 2020. Everything was frozen, but the show went on.

Theo: It was amazing. The performance was amazing. The performance was really powerful, and of course, people came from all over. There were students from high schools in Mobile and all over Alabama. Dance enthusiasts came from everywhere. We had a huge array of people here.

Nell: The performance was a world premiere of Tanya Wideman-Davis and Thaddeaus Davis’ work.

Theo: The dancers pulled people out of the audience to be part of the dance. In the dress rehearsal, unknowingly, the people they pulled out were all McGinnis and Wallace descendants. I got chills.

Nell: As this project has unfolded, my understanding and belief systems have changed. The dance event was huge because the art had the power to get beyond your cognitive space.

These artistic events give your mission of preservation with a purpose a clear shape. Have there been any unexpected challenges in turning that sentiment into reality?

Nell: You know there are some people who haven’t come aboard. The people who have come aboard are all over it, but there’s not full trust in the community. “Let’s see what the white people are doing with us. Are they drawing us in to make money off of us?”

Theo: I think that is the thing. Issues of trust. What is going on, and what is it really about? The longer that we go along, the more likely it is that people will say ok. We just have to do what we’re saying without hidden agendas. We just have to do that with time. Time and consistency are going to help.

And also one other thing is that there are people who should and could support us, but they don’t. That has been a little disappointing. But you know you can’t do anything. I know I shouldn’t care, like, who cares, but I care. You get over it and go on to the people who do support you.

Nell: When I gave the house to the organization in early 2019, our family was sure not to ask anybody for money to fix the place up. We didn’t want to burden the organization or community. Our first annual fundraising campaign actually launched last year. We’ve got some new board members and funding opportunities that I think will help us raise some money so we can build a cottage on-site that will support artists in residency and have indoor plumbing.

The power of place can be unifying. But in this place, with brutally contrasting lived experiences, how do you take that truth and shape it into something uniting?

Nell: Everything we do is directed towards that. We reckon with it and confront it.

Theo: Exactly that. You have to confront it. You have to recognize and reckon. Come together and reconcile. And we’ve done that through the homecomings and the house itself to give it a different chapter. In the sense of rough chapters, it’s had bad chapters, and it’s up to us to write new chapters. We want to leave it raw and open. We want to fill it with art, music, ideas, and discussion. Now we are creating new chapters.

Nell: Theo says only the good ghosts stay. Really though, the atmosphere has literally changed… for the better. I’m sensitive to environments. This one has changed.

What are you most proud of in your journey at The Wallace House together?

Nell: Our relationship is one thing I’m most proud and happy about. And when the house had music in it. Life was here, and it was an “oh my god” moment.

Theo: That the house is living and that we have the opportunity to be an influence on other lives and the young people coming here to read and discuss. I watch people in this very room talk about things that happened to them and see things change.

So Nell talked about our relationship. We’re finally close, even though we’ve had a common connection for years. When I tell you we’re really family, we’re family now.

What are you hopeful for? What are you fearful of?

Nell: Hopeful for the new narrative and hopeful for reconciliation. We may not all get to the promised land, but we’re on the way.

Theo: Fearful… probably of the buy-in. It’s one of the things I’m anxious about. But it’s coming. And money. Making sure we have the money to do all the things we want to do.

How do you think more places with violent histories can change their purpose?

Theo: I think they have to start with discussion. And say, ok, this is real. This happened, but we can take this and change the narrative. I think we can be an example of how to change the narrative. Then I think that’s what we do. You start with a discussion, and you begin to do the work and acknowledge what happened. And ask, how do we move forward?

Nell: We’re following the models of truth and reconciliation from across the world. We’ve just added art to that model.

Can you share upcoming events and programs folks should know about here?

Nell: The dance event is coming back in August. They do site-specific work. And they’ll repeat Migratuse Ataraxia in August and the new Migratuse Revisited in March. We’re so excited!

Salaam Green is going to be our poet-in-residence this year. And she will write poems around the descendants. That is so great. She’ll do spoken word and a coffee table book.

We also have a program with the AL Writers Forum. Salaam is their teaching writer at the local Vincent Middle School, and we collaborate to discuss different points of history in the house. It’s the second year students have read their poems from the Wallace House steps. Theo’s two daughters have been in that class.

We want to bring music to the house too. Also, right now, we’re events based, and in the future, we hope to have the house open more regularly.

Finally, we are going to rename the organization. It will be known as The Wallace Center for Arts and Reconciliation. That better honors the black Wallace descendants.