Interview by Tonia Trotter

Photos by Ambre Amari

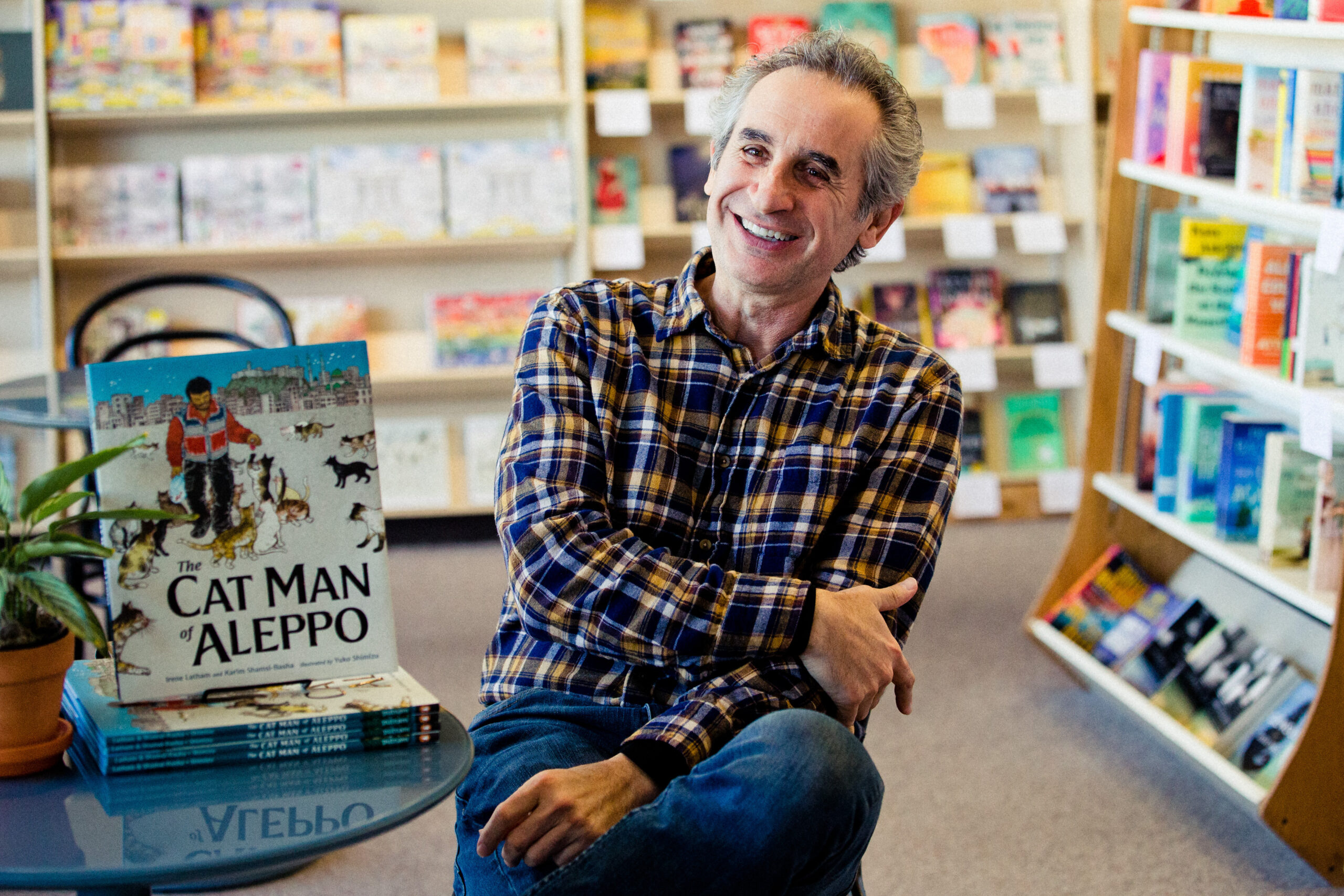

Birmingham writers Irene Latham and Karim Shamsi-Basha are the authors of The Cat Man of Aleppo, recipient of a 2021 Randolph Caldecott Honor — an award presented annually recognizing the most distinguished American picture books. The children’s book, illustrated by artist Yuko Shimizu, is based on the true story of Mohammad Alaa Aljaleel, a Syrian ambulance driver whose efforts to rescue and offer a safe haven to abandoned pets during the Syrian Civil War gained international attention. The authors share their early inspirations, their love for poetry, and the message of humanity amidst a war that brought them together for an award-winning collaboration.

Irene, you already had a prolific literary career as a children’s book author before this most recent book. How did you get your start here in Birmingham?

Irene, you already had a prolific literary career as a children’s book author before this most recent book. How did you get your start here in Birmingham?

Irene: I moved to Birmingham in 1984 because my dad got a job here. I went to Hewitt-Trussville high school and then to UAB. I started trying to get published in the poetry market initially, but my heart was always in children’s writing. So I pursued that, and my first children’s novel was Leaving Gee’s Bend — historical fiction set in 1932 and inspired by the quilters of Gee’s Bend. I love writing about Alabama stories, and my book Meet Miss Fancy is about the elephant who lived in Avondale Park during the Jim Crow era.

Karim, you are a seasoned photojournalist and writer. Writing is part of your DNA, but you didn’t pursue storytelling immediately. What led you to take that leap? What role does imagery play in storytelling?

Karim, you are a seasoned photojournalist and writer. Writing is part of your DNA, but you didn’t pursue storytelling immediately. What led you to take that leap? What role does imagery play in storytelling?

Karim: I grew up in Damascus and emigrated from Syria in 1984. I attended the University of Tennessee and got a degree in mechanical engineering, but that was not my passion… or skillset. My dad wanted to say, “My son is an engineer,” and he pushed me to pursue that — even though he was a writer himself. He was the Poet Laureate of Syria for about a decade. I mailed him my diploma so that he could hang it in his office, and he did! But I’ve never actually worked in that field!

I fell in love with photography, and I worked as a photojournalist for many years before I started writing in 2005. The written word and images work together to tell stories and move people. Some photographs have changed the world — that image of the “Napalm Girl” in Vietnam helped stop the war.

How did the two of you meet?

How did the two of you meet?

Irene: Karim and I met through literary events. We were both running in that circle — at readings and a poem of his was published in the Birmingham Arts Journal, where I’m the Poetry Editor.

You both have strong ties to poetry — in your upbringing, your inspiration, and your professions. In your words, what power is in poetry?

Irene: I love poetry. I visit schools and teach poetry often. One of the things I try to impart is the power of connection. It didn’t always come naturally to me to share my words. When I was first trying to get published, it felt intimidating to share something so personal. But if you can be courageous, take the leap, and find your voice, your words and experiences can create an intimate connection to your reader.

Karim: I love this verse by William Blake:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

That is poetry. It also makes me think, “Ugh. Why can’t I write that?!” My dad read me love poems instead of nursery rhymes as a child, and that shaped me. I love love, and I love poetry. Poetry, to me, is combining the best of your heart and brain.

As children’s book authors, what books or early inspirations were influential in your love for literature?

As children’s book authors, what books or early inspirations were influential in your love for literature?

Karim: When I was in the second grade, I read a copy of Tom Sawyer in Arabic. When I finished it, my dad told me to read it in English. I’d only studied two years of English, and I couldn’t finish it at first, but I kept picking it up over the years. I’ve probably read it 100 times. I still pick it up and read it to remember my youth.

Irene: I loved anything by Shel Silverstein or Horton Hatches the Egg by Dr. Seuss. I love elephants, and I love the message of perseverance to this day. My dad was a voracious reader his whole life, and he kept a catalog of all the books he read in a binder that I have now. His encouragement of me and his passion set a foundation for my love of literature.

How did you two come to work together on this joint project? What did it mean to each of you personally?

How did you two come to work together on this joint project? What did it mean to each of you personally?

Irene: I have a fascination with the Middle East because I lived in Saudi Arabia for a couple of years as a child. Some of my earliest memories are from there, and the Arab people are very dear to me. In 2016, I remember following the news about the siege on Aleppo. There was something awful happening every day. Through social media, this story about Alaa came to my attention.

I immediately thought of Karim! I reached out and asked him if he would collaborate with me. At the time, most of the media coverage was about Syrian refugees. I kept wondering, “What about the people who stay behind?” Not everyone chose to leave, and many couldn’t leave. It felt important to share something about the people who stay during a war.

Karim: I’m embarrassed to admit that I wasn’t familiar with the story. I didn’t have Twitter, and that is where Alaa had been active and gaining some early attention. When I looked him up, I thought, “OMG. This story is a children’s book if I’ve ever seen one!” But beyond the cats, it’s just a sweet, humane story out of a country torn apart by war.

What we tend to hear in the media about Islam and Arabs revolves around war and terrorism. So, it meant a lot to me to share this tale about humanity, love, and care of these helpless creatures. We did so little. The story was already there.

The Caldecott is awarded to picture books, and the illustrations in The Cat Man of Aleppo play a powerful part in telling Alaa’s story.

The Caldecott is awarded to picture books, and the illustrations in The Cat Man of Aleppo play a powerful part in telling Alaa’s story.

Karim: We have to give so much credit to Yuko Shimizu, the illustrator. The Caldecott is awarded each year to the artist of the most distinguished picture book for children, and without Yuko’s beautiful illustrations, the book wouldn’t be the same.

Irene: Yuko did so much research to help tell this story — not just about what the main character, Alaa, looked like. She wanted to know about the war, the landscape, and even the details of how people dressed and accessorized. As picture book authors, we are dependent on the illustrator. It’s not up to us who gets the job. We just got really lucky.

How involved was Alaa in your retelling of his personal story?

Karim: When I first called Alaa to ask if we could write about him, he was flabbergasted that we were interested! I wanted to get the smells, sights, and feeling of where he lived — what he ate and wore each day. We spoke at least every other day for two to three weeks while we were writing the book. There’s an eight-hour difference, and sometimes he would call me at 3 am. I would wake up thinking it was an emergency, but he just wanted to chat!

Creating change can feel overwhelming. Many of us struggle with thinking, “What impact can I have?” But this story beautifully illustrates how one person can start a ripple effect. Beyond the retelling of this true story and spotlighting Alaa’s mission, what is the message you hope to impart with this book?

Creating change can feel overwhelming. Many of us struggle with thinking, “What impact can I have?” But this story beautifully illustrates how one person can start a ripple effect. Beyond the retelling of this true story and spotlighting Alaa’s mission, what is the message you hope to impart with this book?

Irene: The power of kindness — how one small act can create change. Alaa’s not a wealthy man. He chose to spend his money to help these cats and his community. That can happen anywhere. Alaa’s simple and personal generosity inspired a worldwide community to come together. It was like a beacon of light — something started by one man that led to a groundswell of support that created real change. I think that’s an important lesson.